Programming with physics

September 4th, 2009 at 11:06 pm (Computers, Cooking, Technology)

Programming is the art of working out the logic needed to obtain some desired behavior from a system, such as a computer. I’m so used to achieving this with symbols, variables, and control keywords that it hadn’t really occurred to me that the same process has been used since long before computers were invented. Mechanical devices are “programmed” by specifying their physical design, and their behavior is “executed” with physics, not a CPU.

This came to me while I was reading a children’s book describing how a toaster works. What is the job of a toaster? To lie dormant until bread is inserted, then heat up for an appropriate amount of time, then automatically turn off and pop the toast up for easy removal. If I were going to create my own toaster, I’d go at it from a computer-logic perspective: acquire a sensor to measure the current toastiness of the bread (perhaps just its temperature), and then program a tiny embedded chip to respond when the sensor exceeds the desired threshold, at which point the toaster would send a command to the release lever so that the toast would be ejected. But is that how toasters are designed? No!

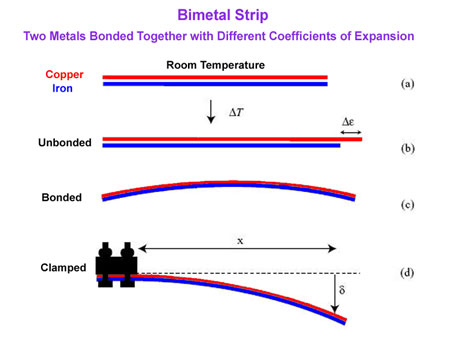

Toasters are a complete marvel of physics-based programming. There is no embedded chip, no logic to specify, no commands. Instead, the toaster relies on a bimetal bar, which bends to the left or right depending on the temperature, because its two metals expand at different rates. (I first encountered bimetallics when I asked my dad how our thermostat worked.) The same current that heats the toaster coils flows through this bimetal bar, and it gradually bends to the side, until it nudges the “heat-up lever” out of contact and instead engages the “cool-off lever”; as it cools back down and straightens, it then releases the cool-off lever which allows the spring-loaded release to pop the bread up.

Toasters are a complete marvel of physics-based programming. There is no embedded chip, no logic to specify, no commands. Instead, the toaster relies on a bimetal bar, which bends to the left or right depending on the temperature, because its two metals expand at different rates. (I first encountered bimetallics when I asked my dad how our thermostat worked.) The same current that heats the toaster coils flows through this bimetal bar, and it gradually bends to the side, until it nudges the “heat-up lever” out of contact and instead engages the “cool-off lever”; as it cools back down and straightens, it then releases the cool-off lever which allows the spring-loaded release to pop the bread up.

Got that? There is no timer in your toaster! (Unless you have some new-fangled version that does in fact use a computer chip.) The timer effect is achieved by simple physics. This is an entirely different kind of programming which must have originally required a lot of trial and error: how long should the bimetal bar be? How thick? Which metals should be used, to get the right differential lengthening? And then there’s the clever puzzle of how to set up the system of levers so that the bending of the bar triggers them in the right order, purely mechanically.

I had always wondered why toasters don’t let you specify a toasting duration, instead of trying to figure out what a unitless dial that goes from 1 to 10 really means in terms of toastiness. Wikipedia relates that early toasters did have timers you manually set, but this caused problems because the first piece of toast needs longer than subsequent ones to achieve the same done-ness. Using the bimetal bar as a toast-proxy works better because it reflects the thermal properties of the heating elements and naturally adjusts the toasting time to fit.

This cleverness isn’t just about toasters: it’s alarm clocks and vending machines and cameras and all sorts of other devices. This kind of “programming” reminds me of dominoes: setting up all the pieces so that they fall into the right places at the right time. What contraints under which to operate! What an interesting development environment!

Maybe I’ve been living in the computer world for too long.

Next up: The transparent toaster.

Evan Dorn said,

September 5, 2009 at 6:31 am

On the other hand, a toaster with a sensor of some sort would be extremely handy: I have to game the dial on my toaster to get appropriate results based on whether or not I am starting from frozen bread. Much of my bread is kept in the freezer – which works great for toast, not as much for sandwiches – but it throws off the bimetal “computation”. :-)

The problem of the timer-based toaster becomes quite evident when you try to toast sequential servings in a toaster oven: second and later batches will burn because the heating elements start off well above room temperature.

I am continually amazed with this kind of physical programming: this history of engineering in the 19th and 20th centuries is full of genius examples. Cheap computation was not available, so clever physical computation was used. In one of the (to my mind) most astonishing examples, heat-seeking guided missiles were designed starting in 1946 – about 35 years before miniaturized computation became available, and using only a single sensor. How? By bouncing an IR signal from a lens off a spinning angled mirror, and using the timing and strength of the resulting pulses to drive a simple guidance circuit. The angle of the mirror when the sensor receives the pulse tells you the direction of the target. The duration of the pulse tells you how close the target is to the central axis. The entire setup has only a few very simple circuit elements. And they didn’t just chase – they would correctly *lead* a target because they measure the time-derivative of the target’s position.

wkiri said,

September 5, 2009 at 9:23 am

Good point: the bimetal bar setup only works if the bread starts at the same initial temperature each time.

Wow, the heat-seeking missile sensor is pretty amazing, too. What’s interesting is that unlike computer-based logic programming, physical programming must work with the constraints of the particular physics of our universe, so wouldn’t “port” well to other universes. But I guess that’s not much of a practical concern right now. :)

LearningNerd said,

September 5, 2009 at 11:29 am

Cool! I had no idea toasters worked because of such a simple phenomenon. Very interesting read!

Speaking of programming, I just decided to take a computer science 101 class. :) Seems like it might be fun. They’re using C++, which I know nothing about. What sort of computer programming experience do you have? Any tips for a newbie?

Jim in PA said,

September 6, 2009 at 5:39 am

Nice post. Reminds me of a story …

(Classic bit of CS humor follows.)

http://www.avdf.com/jan98/hum_h001.html

Kamen Yotov said,

September 7, 2009 at 8:29 pm

After so many years of programming and despite overeducation on the subject, I am still in awe of how mechanics works… Sometimes I just think it is plain harder to use physics instead of keywords and variables…