The American Civil War: Motivations, soldier parole, and the Supreme Court

October 5th, 2018 at 7:16 pm (History, Politics)

I recently attended a lecture at the Huntington by Prof. Emeritus Gary Gallagher of the University of Virginia. He is visiting the Huntington and doing research for his next book. His lecture was on the Civil War, one of his personal areas of expertise. And let me tell you, it is so fun to listen to someone who sincerely *gushes* about their area of expertise. Prof. Gallagher has spent decades studying and sharing his analysis of the Civil War. He’s written eight books so far and is still going strong. Prof. Gallagher lectured without any visual aids, reading from sheets of notes – but the lecture was far from boring. It is clear that he *loves* talking about the Civil War! So passionate!

I took away several interesting thoughts from his lecture. First, he exhorted us not to refer to the “North” and the “South” but instead to “The United States” and “The Confederacy.” Think for a bit about what that means. :)

He also argued that the Civil War was primarily fought over the issue of Union, not Abolition (slavery), although over time historians have shifted to placing more weight on the latter. “Union” here refers to philosophy and politics. One might reasonably ask, if 10 or 11 states wanted to leave the Union, why not just let them? Why did the United States go to bloody war to fight to keep states that didn’t want to be there? Because, he argued, the United States’ “Great Experiment” was threatened. What is a democratic republic if members can simply opt out when they don’t like the outcome of an election? Wouldn’t that prove that our form of government was unworkable? People fought to keep the nation together, which on the face of it sounds a bit abusive. But then again, what war isn’t?

There was also an economic rationale. The Confederacy consisted of the richest states (in terms of per-capita white wealth). South Carolina and Mississippi between them controlled $3B of the economy, while northern industrial activity collectively spanned only $2B. Letting the Confederacy secede would be an economic blow.

Another fascinating topic covered in this lecture were the “parole” arrangements. Neither side wanted to take or be burdened with prisoners of war. So after each battle, they would tally up how many each side captured, and if the numbers were equal, they exchanged prisoners back; but if they were unequal, the extra prisoners would be returned as parolees. These men signed agreements that they would become non-combatants. They were kept in prison camps *on their own side*. They could be re-activated as combatants if their side captured more men from the other side (since then they could be “exchanged”). Imagine!

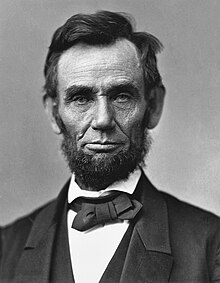

And finally, Prof. Gallagher noted in passing that President Abraham Lincoln appointed no less than *five* Supreme Court Justices during his presidency. The first was due to a vacancy when he assumed office. Then Justice McLean died and Justice Campbell resigned to join the Confederacy. In 1863, Congress apparently expanded the court to hold 10 Justices (!! The Constitution does not dictate the size of the Court) so he got to appoint another one. Then Justice Taney died, bringing the total Lincoln appointments to five. This is astonishing, and no doubt fueled the Confederacy’s ire. Consider the implications of such an occasion in the light of today’s politics.

And finally, Prof. Gallagher noted in passing that President Abraham Lincoln appointed no less than *five* Supreme Court Justices during his presidency. The first was due to a vacancy when he assumed office. Then Justice McLean died and Justice Campbell resigned to join the Confederacy. In 1863, Congress apparently expanded the court to hold 10 Justices (!! The Constitution does not dictate the size of the Court) so he got to appoint another one. Then Justice Taney died, bringing the total Lincoln appointments to five. This is astonishing, and no doubt fueled the Confederacy’s ire. Consider the implications of such an occasion in the light of today’s politics.