Hand signs that convey sound

September 4th, 2016 at 10:54 pm (Language)

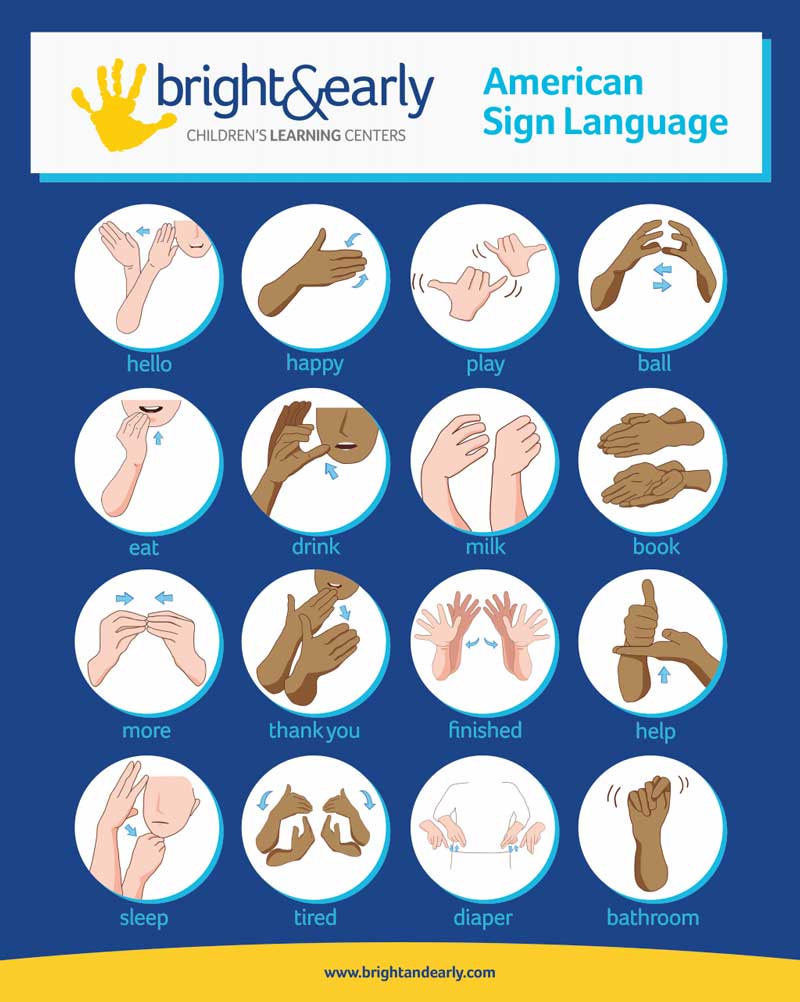

Sign language is a way to communicate with symbols: each gesture has a particular meaning.

But don’t be misled by these simple examples; sign language isn’t simply a signed form of English. Its grammar and usage are quite different. People who grow up Deaf and learn, say, American Sign Language (ASL) as their first language must learn English as a second language.

One strategy to help bridge this gap is “cued speech”, in which the speaker communicates with both voice and signs simultaneously, but the signs are used to convey sound (phonemes), not meaning. As Wikipedia says, “It adds information about the phonology of the word that is not visible on the lips” and can therefore help improve lip reading skills as well (a similar mouth shape could make more than one sound, like “b” and “p”, so the listener can distinguish “bear” and “pear”).

Here’s a short video:

This got me thinking about the ways that we communicate in writing. For example, in Japanese, kanji is a symbolic language like ASL (characters indicate meaning). Hiragana and katakana are phonetic (spelled the way they sound). It can be difficult to remember how to pronounce all of the kanji, even for native speakers (and younger folk may not have encountered a particular kanji yet). So it is common (e.g., in newspapers) to annotate a kanji with its pronunciation using tiny hiragana letters above it (called furigana), to help you pronounce it. Rather like cued speech, but for text!

From this perspective, an alphabet is a curious thing. It’s not (quite) phonetic (at least in English), and it’s not symbolic; letters have no independent meaning. Yet it is very versatile, and just 26 letters suffice to allow us to represent all of English. Learning correct pronunciations for otherwise identical spellings, however (words ending in “ough” such as through, tough, though, etc. being the canonical example), is left up to the reader.