July 20th, 2024 at 6:18 pm (Government)

I’ve heard of small businesses, but the other day it occurred to me that I wasn’t sure how we actually determine whether a business is “small.”

I figured the Small Business Administration must have a definition, to determine who falls into their jurisdiction. And sure enough, here’s where the SBA defines small businesses. This matters because if your business is “small”, it can qualify for certain loans and other opportunities that only small businesses can access.

I figured the Small Business Administration must have a definition, to determine who falls into their jurisdiction. And sure enough, here’s where the SBA defines small businesses. This matters because if your business is “small”, it can qualify for certain loans and other opportunities that only small businesses can access.

In general, they use a threshold on either “average annual receipts” or on the number of employees. But here’s where it gets interesting. If you click through to the table of “small business standards”, you will see that the threshold is different for each industry! In 41 pages! So for example, a chicken egg business qualifies as “small” if it has less than $19M in annual receipts, while a sugar beet farm making that much would not be small (it must make less than $2.5M). In contrast, a nuclear power plant with fewer than 1150 employees is “small”, but a geothermal power plant must have fewer than 250 employees.

There’s no rationale given for how these thresholds were chosen, so I don’t know how much work is involved, but tailoring thresholds for every one of these business areas seems like it must be quite tedious. They are updated once or twice a year. I’m thinking it’s more than a simple formula, since otherwise they could replace the entire table with the formula. Is it the result of negotiation between the SBA and business owners? Is it a capacity constraint, and they pick a threshold so only a fixed number of businesses that year qualify? Do economists weigh in? Mysterious!

Comments

July 14th, 2024 at 8:31 am (History, Language)

Some things come along so early in our language learning that we never think to wonder about them.

Our English numbers “eleven” and “twelve” fall into this category for me. They don’t follow the later “teens” pattern – why not “oneteen” and “twoteen” or some variant?

Recently I learned why! According to etymoline.com, eleven leaves the reference to ten totally implicit and just refers to having one more than [ten], or “one left” (after counting ten):

eleven (num.): “1 more than ten; the number which is one more than ten; a symbol representing this number;” c. 1200, elleovene, from Old English enleofan, endleofan, literally “one left” (over ten)

and the same thing happened for twelve (“two left”):

twelve (num.): Old English twelf “twelve,” literally “two left” (over ten), from Proto-Germanic *twa-lif-, a compound of *twa– (from PIE root *dwo– “two”) + *lif– (from PIE root *leikw– “to leave”)

Note: “PIE root” means for a Proto-Indo-European root that has been reconstructed due to common occurrences across multiple languages.

However, the pattern changes when we get to thrilve thirteen, at least in English. And etymonline notes that

Outside Germanic the only instance of this formation is in Lithuanian, which uses –lika “left over” and continues the series to 19 (vienuo-lika “eleven,” dvy-lika “twelve,” try-lika “thirteen,” keturio-lika “fourteen,” etc.).”

Words are never just words; they impact how we live and think, too. We have separate terms for kids in their “tweens” (before 13) and “teens” (13+). Those terms carry different expectations in terms of maturity, hormonal activity, appetite, need for sleep, etc. Would we have this conceptual division if our numbers, as in Lithuanian, were more regular for the full range 11-19? Maybe, maybe not.

Comments

July 13th, 2024 at 9:06 am (Finances, Technology)

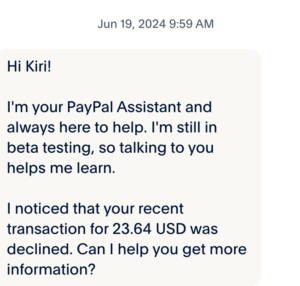

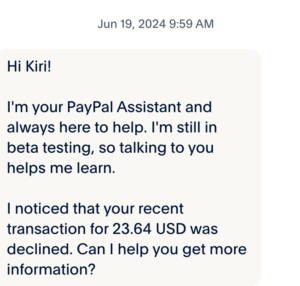

The other day, I couldn’t find some information I needed on the PayPal site, so I engaged with their generative AI chatbot. Before I could type anything, it launched in with this comment:

Hi Kiri!

I’m your PayPal Assistant and always here to help. I’m still in beta testing, so talking to you helps me learn.

I noticed that your recent transaction for 23.64 USD was declined. Can I help you get more information?

I replied “yes” and it gave me a generic link to reasons why a transaction could be declined. It refused to give me any information about the transaction it referred to.

I couldn’t find any such transaction in my account history. I therefore had to call a human on their customer service line to ask. Sure enough, they confirmed there was no such transaction. The chatbot simply made it up.

If I ran PayPal, I’d be terribly embarrassed – no one needs a financial service that generates red herrings like this – and I would turn the thing off until I could test and fix it. Given that this happened to me before I typed anything to the chatbot, you can bet it’s happening to others. If they were hoping the chatbot would save them on human salaries, all it did was create extra work for me and their customer service representative, who could have been helping solve a real problem, not one fabricated by their own chatbot.

I asked if there was somewhere to send the screenshot so they could troubleshoot it. I was told to email it to service@paypal.com . I got an auto-reply that said “Thanks for contacting PayPal. We’re sorry to inform you that this email address is no longer active.” Instead, it directed me to their help pages and to click “Message Us” which… you guessed it… opens a new dialog with the same chatbot.

This careless use of generative AI technology is a growing problem everywhere. A generative AI system is designed to _generate_ (i.e., make up) things. It employs randomness and abstraction to avoid simple regurgitation. This makes it great for writing poetry or brainstorming. But this means it is not (on its own) capable of looking up facts. It is quite clearly not the tool to use to describe, manage, or address financial services. Would you use a roulette wheel to balance your checkbook?

PayPal is exhibiting several problems here, all of which are correctable:

1. Lack of knowledge about AI technology strengths and limitations

2. Decision to deploy the AI technology despite not understanding it

3. Lack of testing of their AI product

4. No mechanism to receive reports of errors, limiting the ability to detect and correct problems

I hope to see future improvement. For now, this is a good cautionary tale for everyone rushing to integrate AI everywhere.

1 Comments

2 of 2 people learned something from this entry.