How to stall a plane

October 31st, 2014 at 4:30 pm (Flying)

Today was my second lesson in flying a plane. There was some uncertainty at the beginning, because the forecast included low-ish clouds (~2000 feet) which would interfere with the type of flying I’m currently allowed to do (i.e., no clouds). But it cleared up a bit so we went for it.

This time, the pre-flight walkthrough to check out the plane only took 1.5 hours instead of 2 hours, and I did the checks instead of watching my instructor do them. The fuel was just under 1/2 full, so I placed a call for the fuel truck. I inspected the wings, the body, the flaps, the ailerons, the elevator, the rudder, and so on. When we were ready, I towed the plane out to the yellow line and we got in.

This time, I got to:

- Talk to the ground and tower controls. My instructor had me practice this first before going “live”, but it was still a bit challenging to be flying the plane and remember what to say and process the response and reply appropriately. My big debut went like this:

“El Monte ground, Skyhawk 19760, row 18. Taxi to active with Charlie.”

- Do the run-up engine tests

- Strobe light – squawk on – throttle full for take-off. And take off!

- Practice steep turns (45 degrees)

- Practice slow flight, at 80 mph

- Practice fast flight, at 110 mph

- Experience a stall!

- Help land the plane

My takeoff this time was much more controlled (we didn’t wobble left/right as much). However, there was a bit of turbulence throughout the flight that made controlling it just a bit more challenging.

I learned that the pilot’s goal in slow flight is different from that of fast flight. In slow flight, you want to keep the speed constant around your goal (like 80 mph). You change the pitch of the plane to control the airspeed. If you want to go up or down in altitude, you give it more/less throttle (and control the nose to maintain desired speed).

In contrast, in fast flight, your goal is to keep the altitude under scrutiny. Here, the pitch controls the altitude. If you want to speed up or slow down (and maintain altitude), you give it more/less throttle (and control the nose to maintain desired altitude).

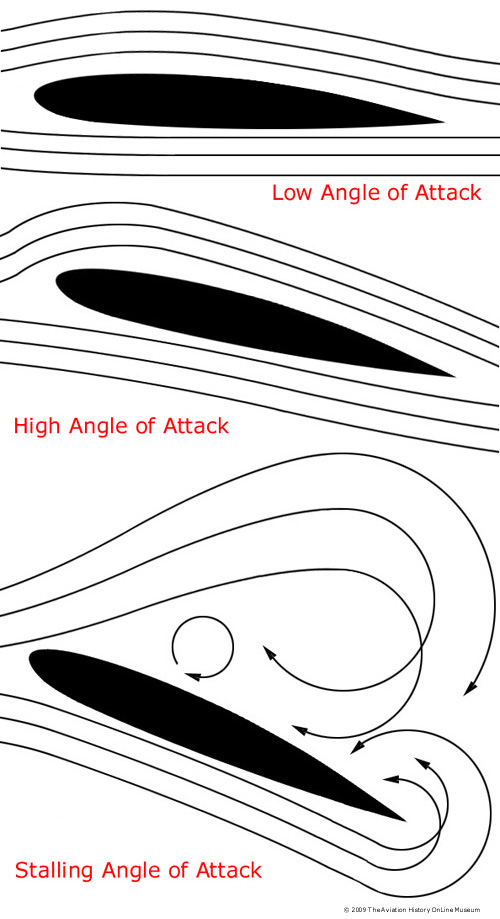

What a stall is like: We slowed down to 70 mph, then down to about 50 mph. The plane was still flying smoothly, but as our speed went down further, the stall horn started to sound. My instructor pulled the nose up on the plane so that it would keep flying at the same altitude, even slower, until we finally stalled. I observed breathlessly, but nothing scary happened; the nose went up a bit and then started down, all on its own. Pointing the nose down reduces the angle of attack, which reduces lift and causes you to lose altitude and gain speed, and suddenly you’re not in a stall anymore. The instructor didn’t do any of that so as to show me how the plane responds on its own; apparently the plane is designed to do this bit of recovery. You can (and likely should) help it along by pushing the nose down more and giving the plane more throttle.

What a stall is like: We slowed down to 70 mph, then down to about 50 mph. The plane was still flying smoothly, but as our speed went down further, the stall horn started to sound. My instructor pulled the nose up on the plane so that it would keep flying at the same altitude, even slower, until we finally stalled. I observed breathlessly, but nothing scary happened; the nose went up a bit and then started down, all on its own. Pointing the nose down reduces the angle of attack, which reduces lift and causes you to lose altitude and gain speed, and suddenly you’re not in a stall anymore. The instructor didn’t do any of that so as to show me how the plane responds on its own; apparently the plane is designed to do this bit of recovery. You can (and likely should) help it along by pushing the nose down more and giving the plane more throttle.

The landing was the most stressful/exciting part of the flight. I think I was already getting a bit mentally tired by that point, and looking forward to being on the ground. As before, my instructor talked me through the final approach and down toward the ground. I stared at the “19” marking the start of the runway to ensure that it stayed stationary (from our perspective) which meant, as he said, that “if we keep going, that’s exactly where we’ll crash.” Then I kept saying,

“Your plane?”

“No.”

“Your plane?”

“No.”

“Your plane?”

“No.”

I was increasingly anxiously waiting for him to take over and handle the transition from air to ground since we hadn’t discussed it and I only have a fuzzy theoretical sense of how that happens. Instead, we had both our hands on the controls and I could feel him guiding it along while I mentally flailed wondering whether I should do something or just be hands-off since I really, really didn’t want to accidentally bump it the wrong way. And then he was leveling off, just a few feet above the runway, and we touched down. He instructed me to brake, and I managed to keep it much straighter this time, and then we turned off the runway to power down. Whew! He reassured me later that he’d felt comfortable having me on the controls and that we weren’t operating outside of a situation he could control or take over, if I did bump the controls or give other random input. Over the next few lessons, I hope to learn exactly how that works and what I SHOULD be doing :)

Later I reflected on a point my instructor made, about how the hardest part of flying is the transitions — between ground and air, or level flight and turns, or slow and high speed flight. This is mainly because you do one set of things with the controls to initiate (and maintain control of) the transition, but then you have to back off and let things settle into the new configuration. There’s a tendency to keep doing the transition action, or do it too long. I realized that this is equally true of, say, driving a car, but we don’t notice it because we’ve already assimilated that practice. As I drove home from the airport, I paid attention to how I automatically start undoing the steering wheel turn well before I arrive at my new pointing, and how I know how much steering wheel turn to give to achieve a desired vehicle turn, which *is* different depending on the speed, even though I don’t think about it consciously. So at some point, the plane control process should also work its way into my muscle response and things will get easier.