July 31st, 2010 at 7:18 pm (Sports, Swimming)

Over the past two days, I’ve had the chance to learn how to wakesurf! Given some expert instruction and tons of assistance (i.e., holding the board steady for me initially, just like training wheels), I was able to stand up on a wakesurfer and ride the wake curl right behind the boat for a good 15 seconds!

First we’d position the board behind the boat so that its front rested on the boarding platform and its tail hung out into the water. I learned to step onto the board with my front foot and lean my weight back out over the board, using the rope, without putting my back foot down until the boat picked up enough speed. It takes some practice to figure this out, but it seems to happen around 6 knots. At that point you can ease your weight fully onto the board (and off the platform) and slide backward, paying out rope gradually, until you’re in the wake curl. At first this felt really shaky to me, because your legs have to figure out how to absorb all of the little bumps and twists of the water while maintaining your balance. Then it started to smooth out, and I stayed up until the board shifted back a little, up onto the wake, and I lost my balance. Also, my posture in this picture could be improved by straightening my torso to make it easier to keep my weight centered over my feet and the board. But hey, not bad for ~8 attempts.

First we’d position the board behind the boat so that its front rested on the boarding platform and its tail hung out into the water. I learned to step onto the board with my front foot and lean my weight back out over the board, using the rope, without putting my back foot down until the boat picked up enough speed. It takes some practice to figure this out, but it seems to happen around 6 knots. At that point you can ease your weight fully onto the board (and off the platform) and slide backward, paying out rope gradually, until you’re in the wake curl. At first this felt really shaky to me, because your legs have to figure out how to absorb all of the little bumps and twists of the water while maintaining your balance. Then it started to smooth out, and I stayed up until the board shifted back a little, up onto the wake, and I lost my balance. Also, my posture in this picture could be improved by straightening my torso to make it easier to keep my weight centered over my feet and the board. But hey, not bad for ~8 attempts.

The goal is to get enough control and comfort that you can actually let go of the rope entirely and just surf along behind the boat. I’m nowhere near that point, but considering that the last time I was really in the water was 1.5 years ago, and that was to learn (belatedly) to swim, I’m thrilled with what I was able to do today! I doubt I’ll ever be a surfer, and I also learned today that I have no innate waterskiing skill, but I’d definitely wakesurf again. It’s fun!

5 Comments

3 of 4 people learned something from this entry.

July 30th, 2010 at 5:45 pm (Productivity, Research)

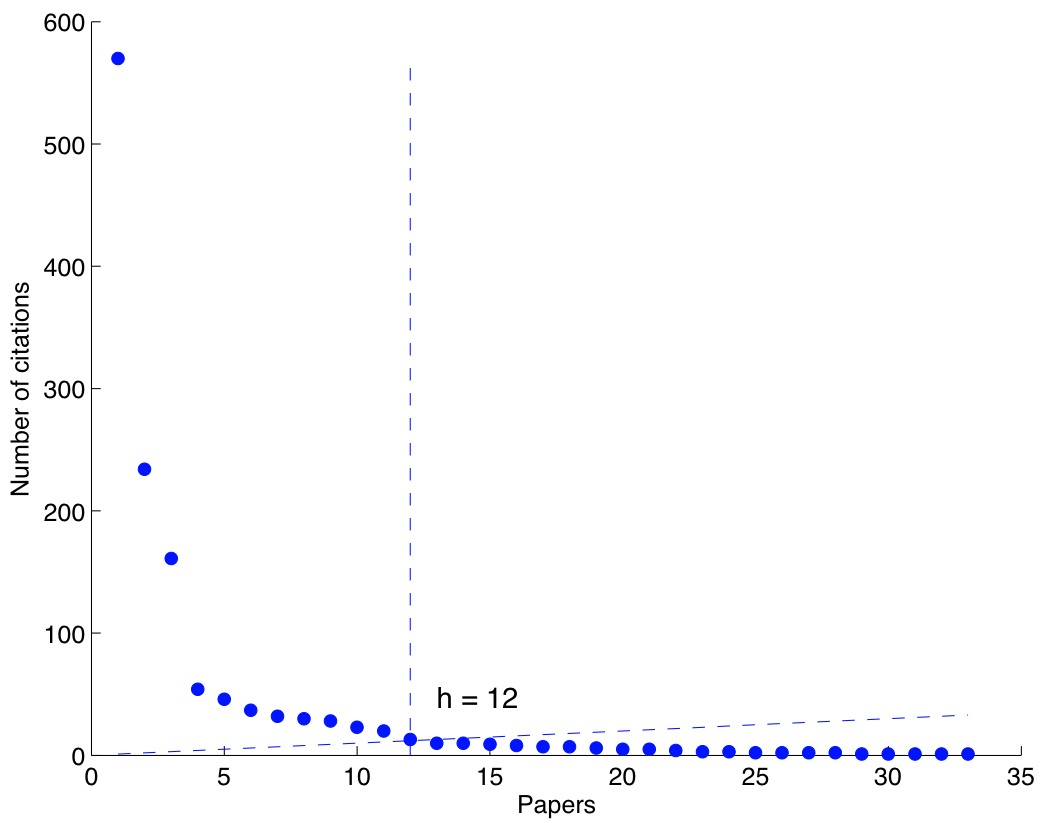

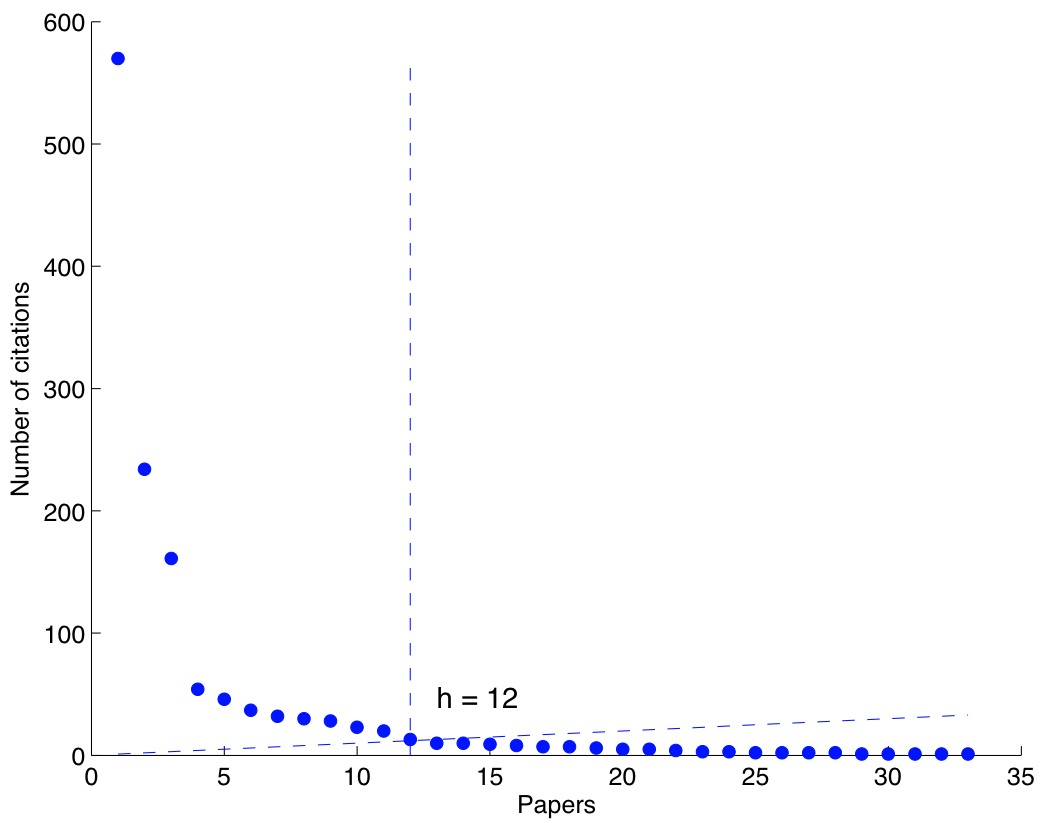

Recently at work, a new person we are hiring was described as having a high “h-index”. I had never heard of this term, so I looked it up later. The h-index is short for Hirsch index and was proposed by Jorge E. Hirsch as a method for quantitatively characterizing scientific impact through publications. It is defined as:

A scientist has index h if h of [his/her] Np papers have at least h citations each, and the other (Np – h) papers have at most h citations each.

Intrigued, I went off and calculated my own h-index, which (using citation data from Google scholar) is 12:

According to the wikipedia entry on the h-index, that’s a decent score for use in “tenure decisions”, while getting up to about 18 might rate a full professorship. Of course, this is a coarse metric with (like all other simple metrics) its drawbacks. It doesn’t factor in the number of other authors on the paper, or whether the citations are self-citations, or how the paper is cited (in a substantive manner vs. a member of a long list of work cited in the introduction). But who doesn’t enjoy a moment of quantitative navel-gazing? Calculate away!

4 Comments

1 of 2 people learned something from this entry.

July 27th, 2010 at 10:11 pm (Crafts)

The next Netflix movie I watched after MirrorMask was Lawrence of Arabia. Wow, what a movie! It leaves an enduring impression due to its sweeping desert vistas, its portrayal of the quirky, passionate, (slightly mad?) character of T. E. Lawrence, and its length. I learned a lot about WWI that I didn’t previously know, such as the role of the Arabs in the conflict.

And in honor of this great movie, I learned how to fold an origami camel. Check it out!

4 Comments

2 of 3 people learned something from this entry.

July 25th, 2010 at 6:01 pm (Poetry, Reflection)

I recently encountered a few poems about poems, in terms of both crafting and appreciating it. These are too delightful not to share (click through for the full versions):

- Introduction to Poetry

… all they want to do

is tie the poem to a chair with rope

and torture a confession out of it…

- The Trouble with Poetry

… the trouble with poetry is

that it encourages the writing of more poetry,

more guppies crowding the fish tank, …

- Sonnet

All we need is fourteen lines, well, thirteen now,

and after this one just a dozen…

All three poems are by the talented Billy Collins, who was the U.S. Poet Laureate from 2001–2003. He is also the man behind Poetry 180, which aims to give high school students a taste of poetry every day of the school year. I admire his dedication to his work as well as his ability to step back and poke fun at it, in a clearly affectionate way.

His meta-poetry is an inspirational reminder of the fun and the value of reflecting on one’s own work, perhaps in the form of the work itself. Maybe I could write a program about programming, or a grant proposal to support work that aims to propose (there already exist slides about how [not to] create PowerPoint slides). Surveying one’s work from a high vantage point can lead to new insights about how to improve efficiency or satisfaction–or even just how to explain what it is and why it matters to a friend or family member.

4 Comments

July 12th, 2010 at 8:11 pm (Computers, Engineering, Technology)

As kids, I think the first encounter most of us have with the idea of an “engineer” is “the person who drives the train”. By the time I started my undergraduate studies, however, I knew that the College of Engineering wasn’t just about driving trains. But I always wondered how a purely functional role could have the same name as what I now saw as an engineer: someone with a very active role in design and problem-solving. Or as wikipedia puts it, “An engineer is a professional practitioner of engineering, concerned with applying scientific knowledge, mathematics and ingenuity to develop solutions for technical problems.”

Recently I picked up some books at the library on steam locomotives and other fascinating train topics. And suddenly, I realized why the train-driver could also lay claim to the title of engineer. Historically, at least, the railroad engineer did not just drive the train. He (these were generally men) also had to be a top-notch engineer, familiar with all of the inner workings of his engine, as he was continually required to maintain, lubricate, tend to, and sometimes even repair the engine. One book noted that the “iron horse” was just as temperamental and required as much attention and grooming as the organic horse it had replaced.

Today, it seems we have a very different view of machines and their users or operators. Most of us who drive cars do not expect to have intimate knowledge of how they work; instead, we hire car mechanics to deal with the details and fix problems. No doubt today’s train engineers are also much more removed from their engines than those of the 1800’s. Computers likewise (or our attitudes about them) have evolved as well, so that users need not understand operating systems and file systems and network protocols, disk scheduling and memory allocation and pipelining, kernels and shells and scripts. Instead, one can hire an IT expert to maintain the machine and fix it when it breaks.

Is this trend a result of the growing sophistication and complexity of these machines, or a shift in our social attitudes towards the desirability of being involved in details? Or both? If it’s an evolution in the machine, are there other machines out there in their infancy and still requiring that the engine be a part of the engineer?

I can see the allure of both the low and high levels on this abstraction spectrum, for computers. I personally enjoy tinkering with the configuration of my computers and knowing what’s going on under the hood, even up to spending hours buried in an ancient Linux machine to get a wireless card working—but sometimes that loses its appeal when I just want things to work. And in truth, when the machine is reliable enough that I don’t need to be checking and tinkering constantly (as with my Mac), I’ve found that I stop doing it. Yet I still feel a tug of curiosity about other machines as well—I’d love to take a basic automotive mechanics course, and learn more about how trains work, and I’m fascinated by pulleys and linkages and astoundingly clever machines of all kinds. But then, I’m an engineer by inclination—or perhaps, I have a wish to be (in a friend’s charming coinage) an “engine-er”: someone who knows and tends and cultivates the engine, akin to a farm-er or a sail-or.

1 Comments

1 of 1 people learned something from this entry.

First we’d position the board behind the boat so that its front rested on the boarding platform and its tail hung out into the water. I learned to step onto the board with my front foot and lean my weight back out over the board, using the rope, without putting my back foot down until the boat picked up enough speed. It takes some practice to figure this out, but it seems to happen around 6 knots. At that point you can ease your weight fully onto the board (and off the platform) and slide backward, paying out rope gradually, until you’re in the wake curl. At first this felt really shaky to me, because your legs have to figure out how to absorb all of the little bumps and twists of the water while maintaining your balance. Then it started to smooth out, and I stayed up until the board shifted back a little, up onto the wake, and I lost my balance. Also, my posture in this picture could be improved by straightening my torso to make it easier to keep my weight centered over my feet and the board. But hey, not bad for ~8 attempts.

First we’d position the board behind the boat so that its front rested on the boarding platform and its tail hung out into the water. I learned to step onto the board with my front foot and lean my weight back out over the board, using the rope, without putting my back foot down until the boat picked up enough speed. It takes some practice to figure this out, but it seems to happen around 6 knots. At that point you can ease your weight fully onto the board (and off the platform) and slide backward, paying out rope gradually, until you’re in the wake curl. At first this felt really shaky to me, because your legs have to figure out how to absorb all of the little bumps and twists of the water while maintaining your balance. Then it started to smooth out, and I stayed up until the board shifted back a little, up onto the wake, and I lost my balance. Also, my posture in this picture could be improved by straightening my torso to make it easier to keep my weight centered over my feet and the board. But hey, not bad for ~8 attempts.