Measure the age of the universe

April 20th, 2009 at 11:31 pm (Astronomy)

The NRAO (National Radio Astronomy Observatory) offers online what just may be the coolest try-this-at-home project ever. How often do you get to do your own cosmology, with no equipment and no training? Well, now you can, by going through the measure the age of the universe tutorial.

Given the observation that all other galaxies are moving away from us (which is observable due to the Doppler effect, which manifests itself as a redshift in the light they emit), and assuming that other spiral galaxies are about the same size as ours (yes, quite an assumption), then using our current estimate of the size of our galaxy, we can convert the apparent size of another galaxy into its distance from us.

Then, we record the distribution of redshifts coming from the galaxy (different parts will shift by different amounts since some may be spinning towards us and some away) and convert those shifts into a velocity. For precision, we look at one particular wavelength (the radio spectral line of hydrogen, here).

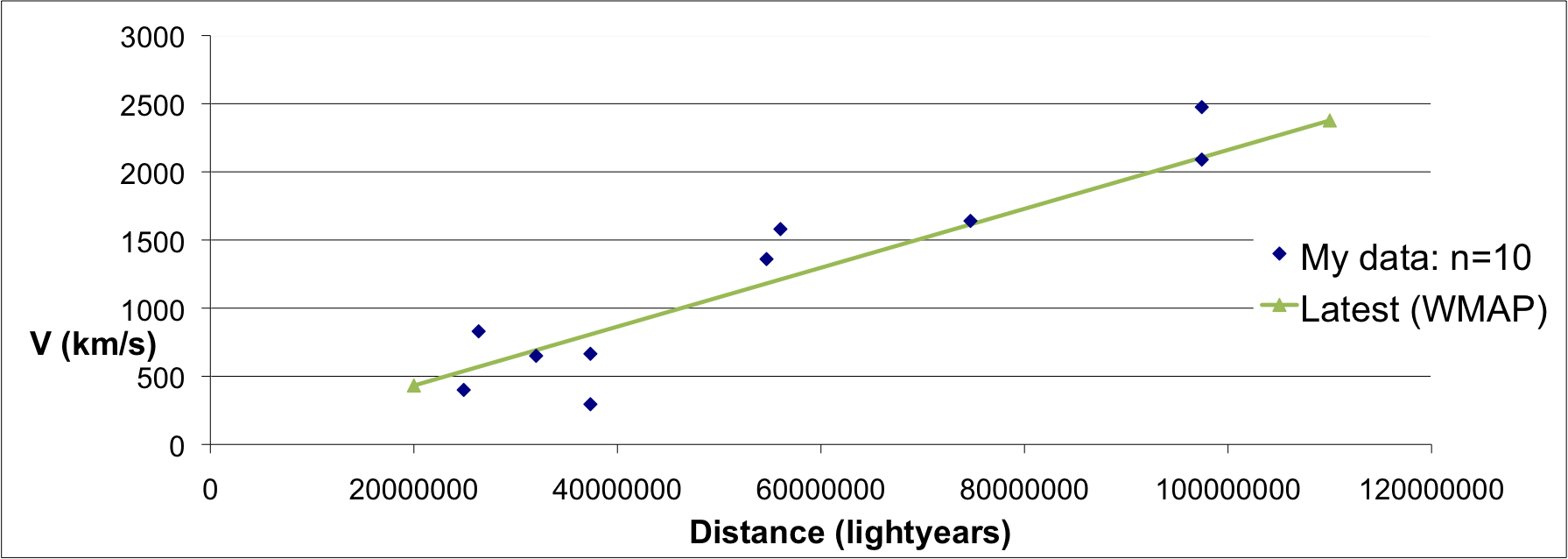

Finally, we plot distance versus velocity to get the relationship between those two variables. Edwin Hubble‘s great discovery, after going through this same process, was that more distant galaxies are more red-shifted, and therefore moving faster — thus, there is some sort of acceleration going on. The slope of a line fit to these data points gives us that acceleration, which is referred to as the Hubble constant, H0. Since this constant (slope) is velocity divided by distance, it has units of 1/time. Therefore, if you take its reciprocal, you get time itself: the age of the universe.

I downloaded the 10 example galaxies provided in the tutorial (and you can, too) and calculated distance and velocity values for each one. I felt more confident in my ability to estimate the velocity (average of the observed values) than for the distance, which is very sensitive to the angular size, which is extremely hard to be precise about with a paper ruler. :) I’m assuming that whoever prepared these examples already adjusted the images so that they all have the same scale. Since not all galaxies are perpendicular to us (some are tilted away), I used the largest diameter I could find. My observations are shown below, plotted against the line obtained using the current best estimate of Hubble’s constant (derived from thousands of observations, not just 10!). While I didn’t get a perfect linear relationship, apparently this isn’t expected due to relativity and other confounding factors. Hubble himself used 46 galaxies and ended up much, much further off (apparently due to “peculiar velocities” and poor calibration on distances).

Each galaxy provides an estimate of the age of the universe. Using these 10 galaxies, my estimates ranged from 10.0 to 39.8 billion years old. Excluding the crazy outlier (NGC 4214, which is the only one with an estimate outside the standard deviation), my estimate of the age of the universe is 14.2 billion years old. Not too far off the latest best estimate of 13.8 billion years!

And what of NGC 4214? It turns out that it isn’t a spiral galaxy at all, which could explain why it didn’t fit with the others. Its redshift indicates that it isn’t going very fast, so shouldn’t be very far away, but it appears to be very small given its proximity. I’m guessing that it’s much smaller than the 10 kpc that was used as the assumed size for all galaxies in this study. In fact, I found that its diameter has been determined to be only 6.7 kpc. So it’s a true outlier, not just due to measurement error.

Science is awesome.