Flying to Twentynine Palms

May 6th, 2017 at 2:32 pm (Flying, Geology)

On April 1, I took my friend Vali for her first flight in a Cessna 172. Vali is a geologist who does a lot of field work in the Joshua Tree area, so we decided to fly to the Twentynine Palms airport (KTNP) which would give us some great aerial views of places she already knows well from the ground.

This was a good chance for me to do some more flying outside of the L.A. Basin. I’ve been working on trying to visit all of the L.A. airports and have now visited 17 of 26 (!). But it’s good to get some longer flights in and more experience with new locations.

Chino Hills with spring green and yellow flower fields

Starting from El Monte, we flew southeast to the Paradise VOR (PDZ), then east through the Banning pass at 7500′. That’s high enough to have some options for landing, but still below the mountain peaks to the north and south, yielding some dramatic views.

Mt. San Jacinto, south of the Banning Pass

We also got a good view of the San Andreas Fault, just east of Palm Springs.

San Andreas Fault

We continued on to the Palm Springs VOR (PSP), then turned northeast to head to Twentynine Palms.

At TNP, we found a cute little pilot’s lounge stocked with water, sodas, and snacks (honor system to pay for fridge items). It also has a microwave and a bathroom. Great place to have our picnic lunch!

TNP pilot’s lounge

TNP has the largest and most visible wind tetrahedron I’ve ever seen. It looks like a huge yellow tent and easily spins around to show the current wind direction. Next to it, the windsock looks small and ineffective.

Windsock and wind tetrahedron at TNP

TNP has runway options for north-south or east-west winds. The larger and more improved runway runs east-west, but the winds at the time of our visit were coming from the north, so we took the smaller one. That meant flying downwind south straight at the rising terrain, then turning for a left base entry to runway 35. It’s 3800′ long, which is plenty, but only 50′ wide, compared to 5500′ x 75′ for the more commonly used runway 8/26.

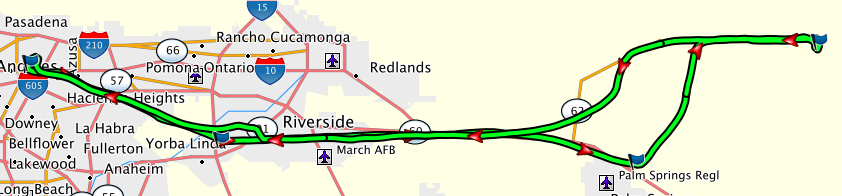

We returned following highway 62 through the Morongo Valley and back west through the Banning Pass at 8500′. I tried to descend a few times as we got closer to the PDZ VOR, but SoCal kept me high to deconflict with traffic. You can see that we didn’t actually reach the VOR but instead did some navigation north around it – SoCal gave us vectors to avoid traffic during that period.

Flight track (click to enlarge).

Both flights were great! We got to see some great terrain and to visit a new airport. It took us about 1.25 hours each way, with a headwind on the way east and a tailwind coming back. It wasn’t a crystal clear day, so there was some distant haze, but still good visibility. One annoyance was that there was light turbulence throughout, which makes the ride a bit less comfortable, but nothing problematic. We overheard someone else coming through the pass who was getting 1000 fpm up- and downdrafts, and we were glad not to have anything that wild!