When thunderstorms get in your way

August 25th, 2018 at 11:01 am (Flying)

On July 6, I flew myself to Palm Springs. This is a short hour-long flight that takes you just outside of the L.A. basin. It turned out to be a record-breaking hot day across SoCal, so the primary things on my mind were keeping the engine cool enough to function and assessing the impact on airplane performance. Palm Springs is only 476 feet above sea level, but given the forecast high of 118 F (!), the density altitude would be above 4000′! (Here’s a handy density altitude calculator.) That means that the airplane would perform as if it were trying to land/take off from an airport at 4000′ elevation. Definitely something to factor in (faster ground speed on landing, longer landing roll, longer takeoff roll, reduced climb performance, etc.).

During preflight, I discovered that the plane’s landing light wasn’t working. I wouldn’t need it for my outbound flight, which was in the morning, but it would potentially constrain my options for a return flight. I decided to proceed and marked it INOP.

I got flight following to Palm Springs at 5500′. I was keeping a close eye on the engine cylinder head temperatures (CHTs), because it was so hot. To keep these values low enough, I had to throttle back and lower the nose, and I was only able to climb at about 150 fpm. In retrospect, I’m thinking that it might have been wiser to not take the plane out on such a hot day!

Along the way, I saw a fire burning at the Cajon Pass. SoCal ATC was busy calling traffic alerts with lots of mentions of firefighting aircraft, which were taking off from San Bernardino. They were all well north of my path.

When checking NOTAMs before my flight, I learned that PSP had changed their ATIS frequency from 118.25 to 124.65 as of May 31. Curiously, the official airport diagram (updated June 21) still had the old frequency. As I got closer, I checked both frequencies until I came through the Banning Pass and could finally pick it up – and sure enough, it was the new frequency. I was glad I’d gotten the NOTAM! Especially when I tuned in and heard that it was 46 C at PSP. I’ve never before heard an ATIS temp in the 40s!

Final approach to runway 13R at Palm Springs

Palm Springs airport was dazzlingly bright and empty. The tower gave me my choice of runways, so I took the big one, 13R (10,000′ long! Why not?). It has a 3000′ displaced threshold, so it feels like it takes a looooong time to get there on final. :) In my flight planning I’d learned that it’s a common mistake to think that the second dark strip to the left is runway 13L. It’s not! It’s a taxiway. I’m glad to learn from others’ tips this way.

I had a nice landing and then was told to “roll out” to taxiway B at the other end, which also took a long time. In this case, landing long (to end up closer to the exit) seemed like a bad idea since if I needed a go-around, I would want all the runway I could get. I parked and got to enjoy a very nice FBO experience. I even got to cool off with a post-flight swim! First time I’ve visited an FBO with a pool!

I had a nice landing and then was told to “roll out” to taxiway B at the other end, which also took a long time. In this case, landing long (to end up closer to the exit) seemed like a bad idea since if I needed a go-around, I would want all the runway I could get. I parked and got to enjoy a very nice FBO experience. I even got to cool off with a post-flight swim! First time I’ve visited an FBO with a pool!

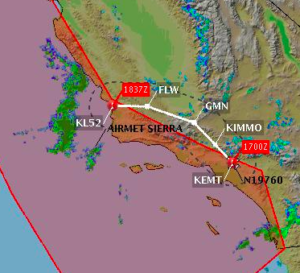

For my return flight, things got a little more interesting. I had planned to fly back on the afternoon of July 7. Waiting until the evening would be better, when it would be cooler, but since the landing light was INOP, I had to get back before sunset. On the morning of July 7, I found that thunderstorms were forecast for the afternoon. There was also a big TFR over San Gorgonio, where another fire had started burning. This was also (just) north of my intended route, but it could mean worse visibility due to smoke.

By midafternoon, the METARs were getting hairy, with TS (thunderstorms), LTG (lightning), CB (cumulonimbus), and TCU (towering cumulonimbus). From what I could deduce, a thunderstorm with lightning was raining on Ontario (just north of my path) and cumulonimbus clouds were squatting over March (just south of my path), likely with associated turbulence and up/down drafts that can extend 20-30 miles out, exactly where I would be flying.

These conditions were a clear “do not fly” signal. So I decided to stay an extra night and fly home in the morning, when it would not only be cooler but also be before any afternoon atmospheric drama would develop. Even when rationally you can clearly see that the right decision is to cancel, it still takes (maybe always will take) an effort! But as a bonus, I got to spend more time visiting family, seeing The Incredibles 2, and having a lovely dinner.

The next morning, it was “only” 99 F when I took off. I was assigned runway 13L this time (the short one), which I determined was still long enough (4952′) for my needs. I expected to depart left traffic, but curiously I was told to make right traffic. It felt weird to turn and keep climbing over the departure end of 13R, but I assume there must have been some traffic east of the airport they wanted me to avoid. As I climbed, another plane called in complaining that they couldn’t get the ATIS, and the tower told them about the month-old frequency change. Now I’m wondering if this is a test to see who is actually reading NOTAMs?

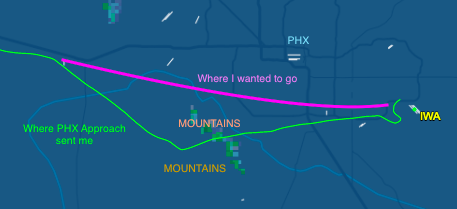

The tower asked me to follow highway 111, which leads northwest away from PSP, at or below 3000′. He seemed happy that I knew where this highway was and could comply. Eventually he handed me over to SoCal and thanked me for my “help” (I still don’t know what he was having me avoid, but happy that he seemed happy). I came back through the Banning Pass, slowly climbing to 4500′, and then SoCal asked me to divert north around Ontario’s airspace. I had planned to go south via PDZ, but okay, I obligingly turned north and spent some time fiddling with the GPS to change my flight plan. In retrospect, I think I could have just communicated that I was heading to PDZ and that might have been fine – they probably just wanted to keep me out of the busy part of ONT’s space. But this way I got to fly over the San Bernardino airport (see left).

The tower asked me to follow highway 111, which leads northwest away from PSP, at or below 3000′. He seemed happy that I knew where this highway was and could comply. Eventually he handed me over to SoCal and thanked me for my “help” (I still don’t know what he was having me avoid, but happy that he seemed happy). I came back through the Banning Pass, slowly climbing to 4500′, and then SoCal asked me to divert north around Ontario’s airspace. I had planned to go south via PDZ, but okay, I obligingly turned north and spent some time fiddling with the GPS to change my flight plan. In retrospect, I think I could have just communicated that I was heading to PDZ and that might have been fine – they probably just wanted to keep me out of the busy part of ONT’s space. But this way I got to fly over the San Bernardino airport (see left).

The rest of the flight was uneventful and I was home in time to quickly pack for a work trip to Sweden the next day!