In Joshua Foer’s excellent book on the art of memory, Moonwalking with Einstein, he mentions the “OK Plateau” as something that all humans learning anything will encounter. This is the stage you reach once you’ve moved past “beginner” and are able to execute a task with some degree of automation. For example, when you first learn to type, you look for and consciously press the right keys. But at some point you learn where they are and can type without looking (or really thinking about individual keys). Foer pointed out something I’ve always wondered — if we tend to get better at something over time, why doesn’t everyone end up being a 100+ wpm touch-typist?

The “OK Plateau” is reached when you are doing a task “well enough” for your needs, and your brain moves on to focus its conscious effort on something else. So even though you might be typing every day (email, reports, documents, forms), you probably will settle into some particular typing speed that never really improves.

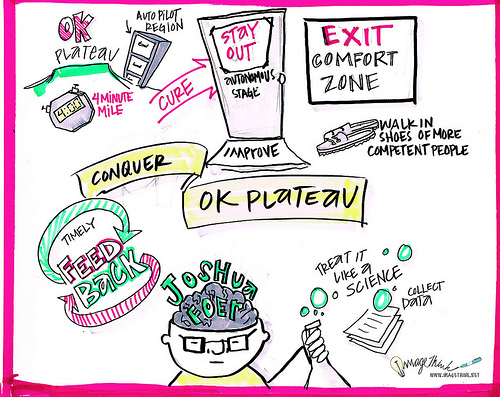

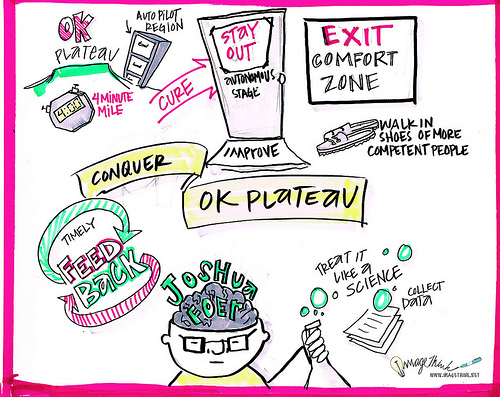

Excellent depiction by imagethink.

This is fine for tasks in which “good enough” is, well, good enough. But there are some things in which you want to become an expert, or at least push your performance to a much higher level. To do that, it seems, you must push yourself back into a conscious awareness of what you are doing and examine and explore where you are making errors or performing suboptimally.

“[Those who excel] develop strategies for consciously keeping out of the autonomous stage while they practice by doing three things: focusing on their technique, staying goal-oriented, and getting constant immediate feedback on their performance.” (Foer)

This means constantly pushing yourself to do more, work faster, tackle harder examples, and so on, and then to learn from your failings or mistakes.

I have been thinking about this in terms of my pilot training. There are significant parts of flying that I can now do with some degree of automation, and it is tempting to declare them “learned” and move my tired brain on to the other big poles. But it is also clear to me that complacency is not something you want to develop in flying – nor in driving – nor anything else that requires a good depth of experience and tuned reflexes. I’ve come across advice in different pilot venues that urge you to continue polishing and refining. How precise can you make your short landing? How precise can you be on airspeed and altitude? If you picked out an emergency landing spot, fly low and actually check it out. Is it as obstacle-free as you thought from higher up?

I expect there is probably a transition you hit once you get your pilot’s license. You go from regular lessons with an instructor (with performance expectations and critiques) to absolute freedom to fly when you want, where you want, with no one watching over your shoulder. At that point, it is up to you to maintain that same level of scrutiny and to critique your own performance. My instructor told me to always have a specific goal when I go out to do solo practice. I’ve encountered the recommendation that, after landing, you give yourself a grade for every flight. What did you do well? What was borderline? What new questions came up that you should research?

Foer describes chess players who learn more from studying old masters’ games (and reasoning through each step) than from playing new games with other players. Studying past games can be more mindful. Pilots can benefit similarly from reading through accident reports to gain knowledge about how things go wrong. AOPA offers a rich array of Accident Case Studies that provide a wealth of scenarios to think through and learn from.

For any hobby or skill, there are similar opportunities to make your practice time more effective at increasing your ability. Instead of playing through your latest violin piece, try doing it 10% faster and see what happens. Try transposing it to a different key on the fly. On your next commute, grade yourself on whether you maintained a specific following distance, how many cars in surrounding lanes you were consciously tracking, how well you optimized your gas mileage, or some other desirable metric.

Employing this approach to everything you do would be exhausting and impossible to maintain. But for those few things that really matter to you, for which the OK Plateau is not good enough, it could be what catapults you to the expert domain. If you’re interested, check out Foer’s short talk summarizing the OK Plateau and his advice for escaping it.