Game design principles that can facilitate learning

February 7th, 2014 at 4:43 pm (Education, Games, Library School)

James Paul Gee, a professor of Reading, decided to explore the world of video games. He picked up a copy of “The New Adventures of the Time Machine” (inspired by the work of H. G. Wells) and was surprised by its difficulty. “Lots of young people pay lots of money to engage in an activity that is hard, long, and complex […] and yet enjoy it,” he wrote in a paper titled “Good video games and good learning”. As an educator, he wondered what elements of these video games could be used to improve learning in a more conventional school setting.

James Paul Gee, a professor of Reading, decided to explore the world of video games. He picked up a copy of “The New Adventures of the Time Machine” (inspired by the work of H. G. Wells) and was surprised by its difficulty. “Lots of young people pay lots of money to engage in an activity that is hard, long, and complex […] and yet enjoy it,” he wrote in a paper titled “Good video games and good learning”. As an educator, he wondered what elements of these video games could be used to improve learning in a more conventional school setting.

Gee identified 16 learning principles that good (effective, successful) games use. I won’t go into all 16 here, but some are interesting to consider, especially in terms of how they might be adopted in schools or universities.

He posits that good games require the player to take on a new identity, inspiring “an extended commitment of self.” The game is a world that you at least partially inhabit. It’s personal. Learning in a class can be the same way, asking you to commit to see the world through the eyes of a physicist or a francophone or a mathematician. Personal investment changes your experience radically from memorizing facts to actively seeing the world in a new way.

Another important principle of effective games is that they give players the opportunity to experiment, and possibly fail, with a relatively low cost. Even if your player dies, you can restart the game. In traditional school environments, failure is often much more public and much more costly: feedback may come in the form of “that’s wrong” instead of “try again.”

Gee also posits that good games are “pleasantly frustrating” in that they keep you within, but right at the edge of, your “regime of competence.” Tasks are doable but challenging. I think this is my favorite regime in which to live, period: challenged but able to make some progress!

A final principle that caught my eye was what Gee calls “well-ordered problems.” Good games give you a series of problems to solve that provide a learning progression: easier tasks first that lead to more difficult ones. In the field of machine learning, some researchers have been studying the best way to present examples to a learner (human or machine). One theory that matches with Gee’s observation is called “curriculum learning”: start with easy examples and progress to more subtle or nuanced ones. Humans tend to use this kind of approach, which perplexes some machine learning researchers since it is provably better to first show the hardest or most ambiguous examples first, because they give you the most information. For example, if I wanted to teach you how to tell whether a child is tall enough to ride a roller coaster, I might point to a boy who is 35 inches tall and say “he’s too short,” and then point to a girl who is 36 inches tall and say “she’s tall enough.” Curriculum learning instead would give you examples like “that man who is 6’4″ is tall enough” and “the 21-inch infant is too short” and only gradually work their way to the harder examples closer to the threshold. However, many learning problems aren’t easy to map to a linear scale in which you just want to pinpoint a threshold, and in those cases, curriculum learning seems to be more natural and more effective.

What else can we learn about learning from how games are designed? Do game designers know something that educators don’t? Not necessarily — but their incentive structure is different, which may lead them to create new kinds of playing, and learning, environments that educators can borrow from.

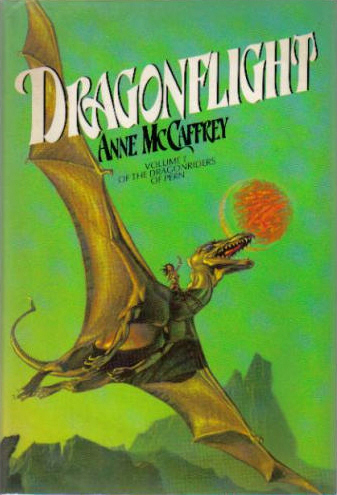

I was quickly captivated by the Pern-based games in which you could create a character who had the chance to be chosen as a dragonrider — every

I was quickly captivated by the Pern-based games in which you could create a character who had the chance to be chosen as a dragonrider — every