September 22nd, 2012 at 9:00 pm (Productivity, Research)

What is your future impact?

Researchers Acuna, Allesina, and Kording decided to use machine learning to find out. They recently published a Nature article, “Future impact: Predicting scientific success,” that describes their method and findings.

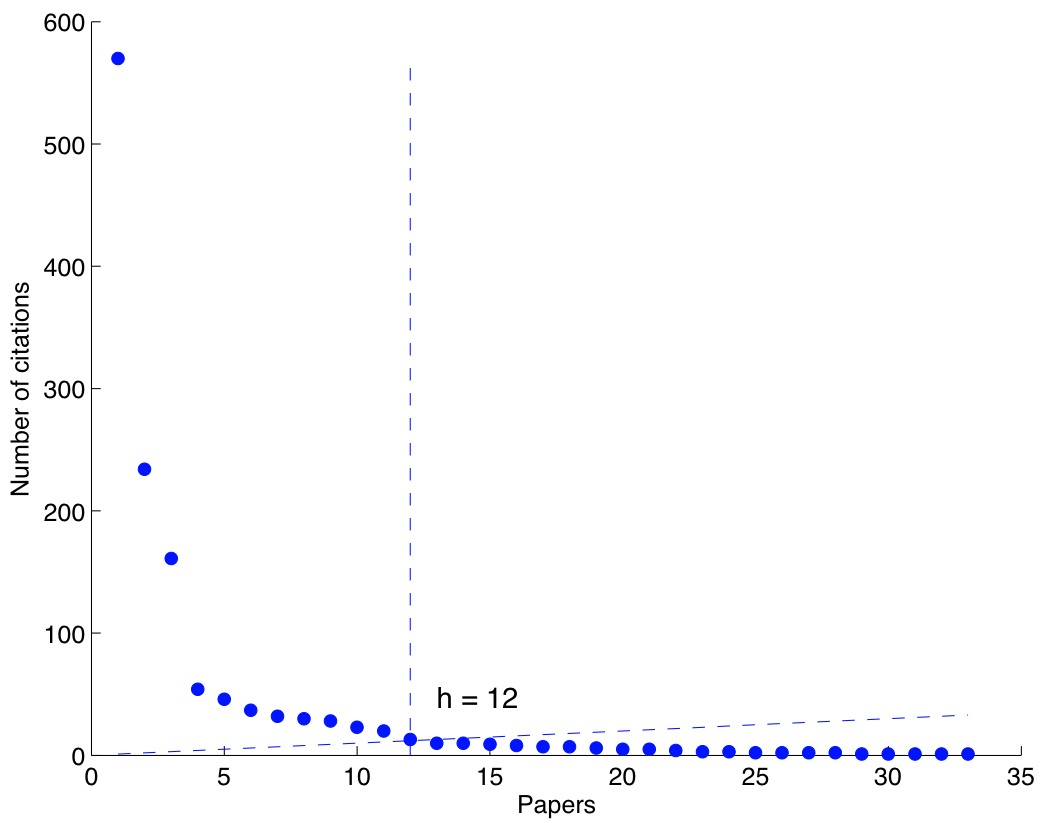

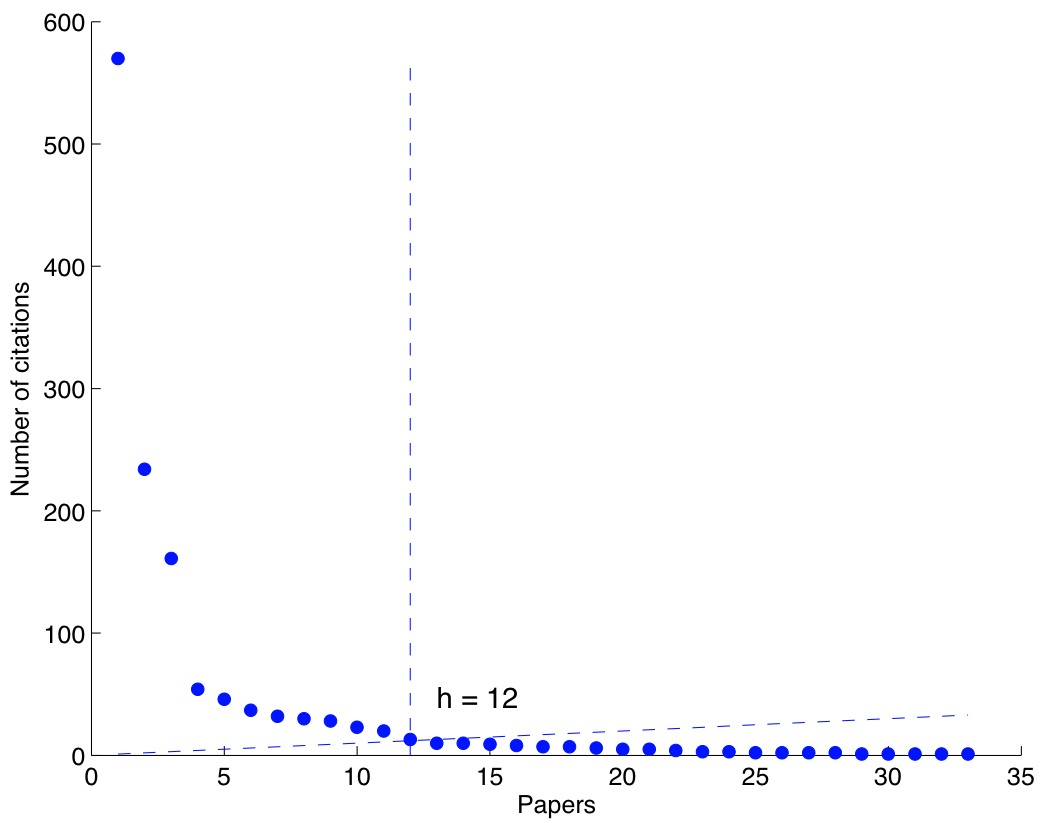

Their goal was to predict a scientist’s future h-index given his or her current bibliographic data. I wrote about discovering the h-index two years ago. Nowadays, Google scholar will calculate this value for you. It’s a measure of research impact, characterized as the number h of your papers that have at least h citations.

Acuna et al. collected data on 3,085 neuroscientists and performed a linear regression on these features:

- n: number of papers written

- h: current h-index

- y: years since publishing first article

- j:Â number of distinct journals published in

- q: number of articles in Nature, Science, Nature Neuroscience, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, and Neuron

They found that this five-factor prediction did better at predicting the future h-index than just using the current h-index itself. Their R2 value for predicting h-index one year into the future was 0.92; five years out, 0.67; and ten years out, 0.48. Their conclusion was that raw h-index numbers were not as predictive as also capturing the scientist’s “breadth” (in j) and the quality of the publication venues (in q).

You can try out their model on your own data, although they note that it is “probably reasonably precise for life scientists, but likely to be less meaningful for the other sciences.” Also, you’ll have to wait the specific number of years to see if it comes true. Or you can plug in your data from a few years ago and see how the predictions match the present. Using my data from two years ago (h-index 12), their system predicts that my h-index this year should reach 19. Google scholar pegs it at 17 right now, so either I am not reaching my proper potential, or their model is wrong. ;)

There’s more than recreational fun going on here. The authors note that h-index values may be used in tenure decisions. In that context, the ability to predict a candidate’s h-index five years into the future could have even more impact—if it were sufficiently reliable. As usual, we can hope that such decisions are made with more than just these impoverished metrics in mind!

2 Comments

May 12th, 2012 at 9:50 pm (Research, Society)

I’ve been impressed with what folks have been able to do at Kickstarter, raising funds to create a product they believe in. In contrast to venture capital or other business investors, Kickstarter contributors are consumers; a vote to support your startup process is a vote for your product. This seems to work well on both sides: consumers get a low-risk way to “shop” for innovative products, and inventors can simultaneously raise funds and test the waters in terms of demand.

So I was intrigued when I came across a Kickstarter-like site… for scientific research projects.

iAMscientist allows researchers to post descriptions of their projects, and interested members of the wider community can pledge funds to support them. Goodbye to lengthy, dense proposals to agencies such as the NSF, NASA, or NIH! Rather than getting your project funded by review from your scientific peers, you instead pitch it to woo the general public.

iAMscientist allows researchers to post descriptions of their projects, and interested members of the wider community can pledge funds to support them. Goodbye to lengthy, dense proposals to agencies such as the NSF, NASA, or NIH! Rather than getting your project funded by review from your scientific peers, you instead pitch it to woo the general public.

I can see merits in exposing the public to new ideas, and getting them personally involved in a way that’s just not possible when the projects are paid for by their tax dollars. But can this actually work? It’s not clear to me that people will be as excited about supporting research as they would be about, say, an e-paper watch.

So what interested me most was what these researchers had come up with in terms of “rewards” for donations, since they lack a tangible product. What is it about what I do, day-to-day, that could be commoditized anyway? The rewards for Bridging Scales in Biology From Atoms to Organisms include a signed thank-you letter, a signed preprint of the resulting scientific paper, a personal lab tour or seminar, acknowledgement in the paper, and patent options. Wow! It had never occurred to me that my autograph on a paper I wrote could be of value. :) And it’s interesting how some of these things (like a lab tour) are things you would expect as a matter of course, if you were to visit, as a researcher yourself. I guess that access is something the general public might be willing to pay for—or at least, that’s Dr. Shakhnovich’s assumption!

My favorite is the reward offered for a $64,000 donation by Dr. Pollack, the chair of the Computer Science department at Brandeis University, for his GOLEM project:

$64000: Endow the lab email and web server.

Half the donation will go to to the research and the other half will endow a permanent fund in the university endowment to provide $3200 per year to maintain and upgrade a server — in perpetuity — upon which my lab will host its website “www.Yourname.Brandeis.edu”. I will personally adopt a new email address thusly: “Pollack@Yourname.brandeis.edu”, and I send and receive a LOT of email!

What are you waiting for? Get out there and support science!

1 Comments

1 of 1 people learned something from this entry.

July 30th, 2010 at 5:45 pm (Productivity, Research)

Recently at work, a new person we are hiring was described as having a high “h-index”. I had never heard of this term, so I looked it up later. The h-index is short for Hirsch index and was proposed by Jorge E. Hirsch as a method for quantitatively characterizing scientific impact through publications. It is defined as:

A scientist has index h if h of [his/her] Np papers have at least h citations each, and the other (Np – h) papers have at most h citations each.

Intrigued, I went off and calculated my own h-index, which (using citation data from Google scholar) is 12:

According to the wikipedia entry on the h-index, that’s a decent score for use in “tenure decisions”, while getting up to about 18 might rate a full professorship. Of course, this is a coarse metric with (like all other simple metrics) its drawbacks. It doesn’t factor in the number of other authors on the paper, or whether the citations are self-citations, or how the paper is cited (in a substantive manner vs. a member of a long list of work cited in the introduction). But who doesn’t enjoy a moment of quantitative navel-gazing? Calculate away!

4 Comments

1 of 2 people learned something from this entry.