Others in my French Translation class have chosen works of literature for their translation projects. Me? I chose a recent article announcing a terribly exciting discovery: the first rocky exoplanet! (As opposed to the “hot Jupiters” and other large gaseous planets.) I found this article on the radio-canada.ca website:

Une première exoplanète rocheuse

(16/9/2009)

Près de 15 ans après la découverte de la première exoplanète en 1995, des astrophysiciens européens ont annoncé avoir trouvé une toute première planète de type rocheuse autour d’une autre étoile que notre Soleil. L’exoplanète Corot 7b avait été observée en début d’année, mais sa composition n’avait pu être établie à ce moment. Sa constitution n’est pas l’unique particularité de Corot 7b. Elle est également la plus petite jamais découverte, avec un rayon équivalent à 1,8 fois celui de la Terre. De plus, c’est la planète la plus proche de son étoile. Elle en fait le tour en seulement 20 heures (correspondant à la durée de son année). Le spectrographe HARPS installé sur le télescope européen de 3,6 mètres de la Silla, au Chili, a également permis d’établir que sa masse correspondait à 4,8 fois celle de la Terre.

Vie impossible

La température dépasse 2000 degrés Celsius sur la face éclairée, puisqu’elle est située à seulement 2,5 millions de kilomètres de son étoile. L’astre pourrait avoir des océans de lave à sa surface. L’autre face, plongée dans la nuit, est glaciale, avec des températures qui plongent sous les -200 degrés Celsius. À titre de comparaison, la Terre tourne à 150 millions de kilomètres du Soleil.

En avril dernier, Gliese 581e avait été présentée comme la plus petite exoplanète. Les découvreurs de Corot 7b estiment que seule la masse de cette dernière est connue, ce qui n’est pas le cas pour Gliese 581e.

Even though my French Translation class is obviously in the humanities, I was a little surprised at some of the students’ reaction to this article — it clearly was perceived as a bit out of place! However, several people commented on how they learned a lot from it: some didn’t even know that we’d discovered exoplanets (!) and others did additional research, reporting (correctly) that we’ve discovered more than 300 of these bodies! So I guess it turned out to be an unexpected chance to sow a little science, and alert others to one of the most amazing advances we’ve made in the last couple of decades (in my humble opinion).

But without further ado, here is my translation:

The first rocky exoplanet

Nearly 15 years after the discovery of the first exoplanet in 1995, European astrophysicists announced that they have found the very first rocky exoplanet around a star other than our Sun. The exoplanet Corot 7b was observed at the beginning of the year, but its composition could not be established until now. Its composition is not Corot 7b’s only distinction. It is also the smallest ever discovered, with a radius equivalent to 1.8 times that of the Earth. Moreover, it is the planet closest to its own star. It orbits in only 20 hours (corresponding to the length of its year). The HARPS spectrograph installed on the 3.6-meter European telescope at La Silla [an observatory], in Chile, has also established that its mass corresponds to 4.8 times that of the Earth.

Life is impossible

Temperatures exceed 2000 degrees Celsius on the illuminated side, since the planet is located only 2.5 million km from its star. The planet* may have oceans of lava on its surface. The other side, plunged into night, is icy, with temperatures that drop to less than -200 degrees Celsius. For comparison, the Earth orbits at 150 million km from the Sun.

Last April, Gliese 581e was presented as the smallest exoplanet. The discoverers of Corot 7b consider mass to be [definitively] known only for Corot 7b, and not for Gliese 581e.

*The word “astre” is translated as “star”, but that makes no sense here; it should be “planet”.

I must say, that final sentence gave me the most trouble! Suggestions about other ways to phrase it are certainly welcome.

In class, we discussed my translation, and I received several suggestions about ways to improve it:

- “Ã ce moment” should have been translated as “at that time” rather than “until now.”

- Consider “duration of its year” rather than “length of its year.”

- Consider breaking the final sentence of the first paragraph into two sentences, as it is rather unwieldy.

- Consider changing “The other side, plunged into night” to simply “The dark side” (for clarity over poetry). I disliked “plunged” myself, because it sounds overly dramatic. If wishing to stick closer to the original, someone else suggested “The other side, immersed in night” (less sense of active motion).

- Apparently “À titre de comparaison” is a stock phrase that means “By way of comparison,” although “For comparison” also works (is probably less formal, though).

After class, I checked how Babelfish and Google Translate rendered this text into English. The Babelfish version is heart-stoppingly bad, beginning with

“Nearly 15 years after the discovery of the first exoplanète in 1995, of the European astrophysicists announced to have found a very first planet of the rock type around d’ another star that our Sun.”

It’s not terrible that Babelfish doesn’t know the word “exoplanète”, but its inability to handle contractions throughout the article is really inexcusable, especially for French! Google Translate’s version is consistently better, but not perfect. The first sentence is rendered:

“Nearly 15 years after the discovery of the first exoplanet in 1995, the European astrophysicists have announced to have found a first-type rocky planet around a star other than our Sun,”

but it failed to catch the negation in the second:

“The COROT exoplanet 7b was observed earlier this year, but its composition had been established at this time.”

(Also humorous is its translation of “581e” as “581st” — subtle!)

I guess I am encouraged that there’s still a need for human translators!

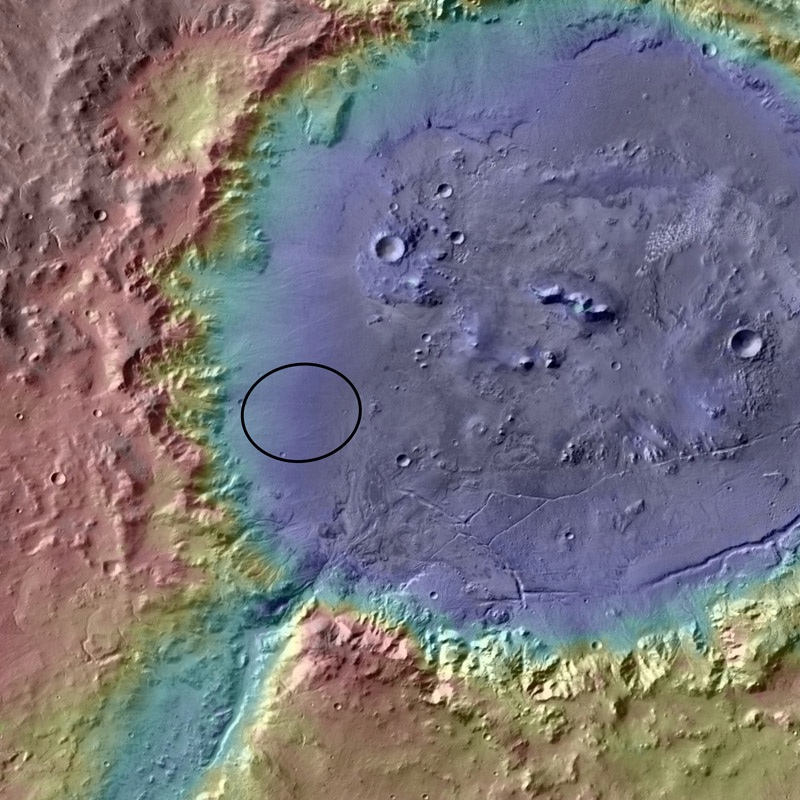

Could it make sense to take a one-way trip to Mars? This notion has been floating around for years, but it got some recent press when Drs. Schulze-Makuch and Davies published a paper titled “To Boldly Go: A One-Way Human Mission to Mars.” Their thesis is that this might be the solution to several of the barriers to a crewed mission, providing among other benefits a major reduction in mission cost (up to 80% reduction, which is pretty dramatic!). This can only be accomplished by shifting our perspective on what such a mission is: not a there-and-back-again jaunt like a trip to the Moon, but the establishment of a sustained presence on Mars, paving the way for future colonists and expeditions. Schulze-Makuch and Davies declare that:

Could it make sense to take a one-way trip to Mars? This notion has been floating around for years, but it got some recent press when Drs. Schulze-Makuch and Davies published a paper titled “To Boldly Go: A One-Way Human Mission to Mars.” Their thesis is that this might be the solution to several of the barriers to a crewed mission, providing among other benefits a major reduction in mission cost (up to 80% reduction, which is pretty dramatic!). This can only be accomplished by shifting our perspective on what such a mission is: not a there-and-back-again jaunt like a trip to the Moon, but the establishment of a sustained presence on Mars, paving the way for future colonists and expeditions. Schulze-Makuch and Davies declare that: